When I was a kid growing up we understood that when people went to work, they did something tangible. We understood what the mailman, policeman, salesman, doctor, dentist, nurse and teacher did. Then a new job emerged – the middle manager. We asked our parents what they did but our parents couldn’t give us a good description. They really didn’t know. They just told us we should become one.

Eventually an image of managers emerged. Managers were smart, well educated, and driven to climb the corporate ladder. In their upper echelon, they develop strategies, attend meetings and conference calls, make decisions, read reports, meet with clients, play golf, have two-martini lunches, drive expensive cars, live in a big houses and belong to a country club.

Since managers were selected and promoted into the management ranks, we assumed they were the best and the brightest in our workplace.

However, in spite of all of the status and air of importance associated with managers, the workforce had a different opinion. They often thought that if a manager disappeared, no one would care; if they even noticed.

Their perspective brought us back to the greatest mystery in business: What does a middle manager really do?

When I entered the male-dominated workplace in the early 1980’s I joined the throngs of people wondering what managers do and why the workplace needed them. I expected managers to interact and supervise their staff but I hardly saw my managers and rarely talked to them. They always seemed to be busy but they didn’t produce anything.

In 1987 I got my first middle management position. I asked my predecessor what he did. He showed me to my new office stacked to the gills with 102 unresolved open project folders and I realized he never knew what he was supposed to do as a middle manager either.

I began to work on my own definition of being a manager. I interacted a lot with my three departments solving our functional problems. We rewrote all of our operating processes and procedures. We tightened communication and coordination. We all began moving in the same direction together and eliminated people going off randomly on their own doing what they wanted. Our performance soared.

Then about 15 months into my job my boss was unhappy in his life so he called me into his office to counsel me. He told me that I didn’t yell enough at my staff. He wanted me to follow his example where he had been yelling at and insulting the men in our weekly staff meeting. He directed me to go down to my Planning Dept. and yell at all the planners.

At least I knew his definition of what a manager does.

So I went down and met with my planners. I told them I was sent there to yell at them and asked them what they would do if I yelled at them like my boss wanted me to. Their answer was: “We will ignore you just like we do him.”

I still didn’t get how men thought about management. At the time I was getting my master’s degree and decided the department head was the perfect person to answer the mysterious question of what a manager in the male-dominated workplace is supposed to do. In response he set me up to take a one-on-one course with a new visiting professor.

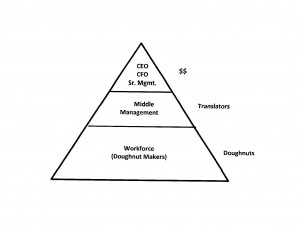

My new professor explained the role of a manager by drawing a diagram based upon Juran’s interpretation of the workplace vertical hierarchy. For some reason I immediately renamed it the Dollars to Doughnuts model.

This model explains how a company should function holistically.

At the bottom of the pyramid is the largest group – the workforce. The workforce is comprised of unskilled, skilled and/or professional workers depending upon the product or service the workplace produces. The workforce can be of any educational level ranging from uneducated unskilled laborers to highly educated, highly skilled neurosurgeons. They use processes and systems to produce the products and services purchased by the workplace’s customers.

I call these people the doughnut makers. They know how to make the doughnuts and how to operate the shop that sells the doughnuts. They live in the world of the doughnut shop and they speak in the language of doughnuts.

At the top of the pyramid are the CEO, CFO and Sr. Management. They represent the company to the outside world. They speak in the universal business language of money. Using the language of money, they can compare themselves not only to other doughnut making companies but to companies in other industries.

Since the top of the pyramid speaks in the language of money and the bottom in the language of doughnuts, there is a communication problem.

For example, a senior manager knows the doughnut shop is short on revenue and is busting some budget lines. So, on his semi-annual scheduled doughnut shop walk-thru he asks the doughnut makers: “What’s going on?”

The doughnut makers tell him about how the doughnut fryers keep breaking down. They have to wait for new parts to come in so that means they are down on fryers. Being short on fryers they have to work overtime in order to make the doughnuts. But that makes the working fryers run longer which means they break down faster. They are also short one person because he is busy dealing with broken fryers. They were so busy dealing with the fryers that the flour and sugar orders got messed up and they had to expedite some deliveries. But then the flour and sugar supplier changed their weekly delivery date based upon their expedited delivery so they ran short the following week. They need him to change it back because it conflicts with their heaviest production day.

This is the truthful answer that drives senior managers right back to their office and to never step foot in a doughnut shop again. The only response the overwhelmed senior manager can offer is the obvious solution: “Get those fryers fixed as soon as possible.”

To this the doughnut maker response is – “Duh. What do you think we are busting our butts trying to do?”

This is why the workforce doesn’t find value in management.

The real problem is that the senior manager asked a question speaking “Money” but the doughnut makers replied speaking “Doughnut.” They don’t understand each other.

What they need is a translator. (That sounds like a communication skill and something women excel at!)

Translation is the real definition of what a middle manager does.

In Juran’s original model, he said that middle managers convert doughnuts into budgets. That is true however it is only a partial definition of translation. I expanded the definition to leverage female traits.

What a middle manager really does is know how to make money making and selling doughnuts. That goes well beyond developing budget lines and tracking monthly whether you are over or under budget.

Making money by making and selling doughnuts requires understanding how the doughnut shop operates and how actions within the doughnut shop impact financials. Very simple examples of translation are:

- An expedited delivery of flour will have a $100 delivery charge

- Two people working two hours overtime will cost $190

- If the shop makes 100 doughnuts per hour doughnuts cost 20 cents to make. If they make 120 doughnuts per hour doughnuts cost 18 cents to make.

Translation begins by focusing on the doughnut shop’s processes and procedures. We want standardized processes and procedures so we have consistent outcomes. When the processes are standardized, the outcomes are consistent and it is easy to see the financial results. With experience we instinctively learn to see what is happening in our doughnut shop and immediately know the financial ramifications.

What many middle managers do is wait for the month-end financial statement, look for discrepancies, then make up stories that sound plausible to explain the discrepancies to senior management. They do this because they can’t translate.

When we become good at translating we don’t have to wait for month-end reports. We see a variation in how the doughnut shop functions and we know in real time what the financial impact is.

This then triggers us to work with our doughnut makers to improve the processes, so the variation doesn’t reoccur. By reducing these variations financial performance improves. For a middle manager this is your claim to fame.

The problem is that many of our workplaces don’t operate through standardized processes even if they supposedly have them. Individual departments or projects tout they are different or unique so the standardized processes wouldn’t work for them.

The real reason this happens is because in the male-dominated workplace men aspire to autonomy – to being independent and doing things the way they personally think is best. Standardization works against everything men are taught about being men. Without standardized processes laying the foundation, male middle managers can’t translate.

Women however, don’t aspire to autonomy. We enjoy and know how to work in groups. Standardized processes don’t threaten us. We enjoy leading from within, not leading from above and dictating downward. This makes us perfectly suited to lead our doughnut shop to map out their processes and then improve their processes.

Translation is the major discriminator between male and female middle managers. It is how women can distinguish themselves and set a new standard for middle management performance.

Translation is also what set us up to move up to senior management and excel there too.

Empowered Women Excel at Translation

To subscribe to my articles Contact Me

Don’t forget to Leave a Comment and Share!

Follow The Woman In The Room on facebook.